In my post on Recurrent Neural Networks in Tensorflow, I observed that Tensorflow’s approach to truncated backpropagation (feeding in truncated subsequences of length n) is qualitatively different than “backpropagating errors a maximum of n steps”. In this post, I explore the differences, implement a truncated backpropagation algorithm in Tensorflow that maintains the distribution between backpropagated errors, and ask whether one approach is better than the other.

I conclude that:

- Because a well-implemented evenly-distributed truncated backpropagation algorithm would run about as fast as full backpropagation over the sequence, and full backpropagation performs slightly better, it is most likely not worth implementing such an algorithm.

- The discussion and preliminary experiments in this post show that n-step Tensorflow-style truncated backprop (i.e., with num_steps = n) does not effectively backpropagate errors the full n-steps. Thus, if you are using Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation and need to capture n-step dependencies, you may benefit from using a num_steps that is appreciably higher than n in order to effectively backpropagate errors the desired n steps.

Differences in styles of truncated backpropagation

Suppose we are training an RNN on sequences of length 10,000. If we apply non-truncated backpropagation through time, the entire sequence is fed into the network at once, the error at time step 10,000 will be back propagated all the way back to time step 1. The two problems with this are that it is (1) expensive to backpropagate the error so many steps, and (2) due to vanishing gradients, backpropagated errors get smaller and smaller layer by layer, which makes further backpropagation insignificant.

To deal with this, we might implement “truncated” backpropagation. A good description of truncated backpropagation is provided in Section 2.8.6 of Ilya Sutskever’s Ph.D. thesis:

“[Truncated backpropagation] processes the sequence one timestep at a time, and every k1 timesteps, it runs BPTT for k2 timesteps…”

Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation uses k1 = k2 (= num_steps). See Tensorflow api docs. The question this post addresses is whether setting k1 = 1 achieves better results. I will deem this “true” truncated backpropagation, since every error that can be backpropagated k2 steps is backpropagated the full k2 steps.

To understand why these two approaches are qualitatively different, consider how they differ on sequences of length 49 with backpropagation of errors truncated to 7 steps. In both, every error is backpropagated to the weights at the current timestep. However, in Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation, the sequence is broken into 7 subsequences, each of length 7, and only 7 over the errors are backpropagated 7 steps. In “true” truncated backpropagation, 42 of the errors can be backpropagated for 7 steps, and 42 are. This may lead to different results because the ratio of 7-step to 1-step errors used to update the weights is significantly different.

To visualize the difference, here is how true truncated backpropagation looks on a sequence of length 6 with errors truncated to 3 steps:

And here is how Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation looks on the same sequence:

Experiment design

To compare the performance of the two algorithms, I write implement a “true” truncated backpropagation algorithm and compare results. The algorithms are compared on a vanilla-RNN, based on the one used in my prior post, Recurrent Neural Networks in Tensorflow I, except that I upgrade the task and model complexity, since the basic model from my prior post learned the simple patterns in the toy dataset very quickly. The task will be language modeling on the ptb dataset, and to match the increased complexity of this task, I add an embedding layer and dropout to the basic RNN model.

I compare the best performance of each algorithm on the validation set after 20 epochs for the cases below. In each case, I use an AdamOptimizer (it does better than other optimizers in preliminary tests) and learning rates of 0.003, 0.001 and 0.0003.

5-step truncated backpropagation

- True, sequences of length 20

- TF-style

10-step truncated backpropagation

- True, sequences of length 30

- TF-style

20-step truncated backpropagation

- True, sequences of length 40

- TF-style

40-step truncated backpropagation

- TF-style

Code

Imports and data generators

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from tensorflow.models.rnn.ptb import reader

#data from http://www.fit.vutbr.cz/~imikolov/rnnlm/simple-examples.tgz

raw_data = reader.ptb_raw_data('ptb_data')

train_data, val_data, test_data, num_classes = raw_data

def gen_epochs(n, num_steps, batch_size):

for i in range(n):

yield reader.ptb_iterator(train_data, batch_size, num_steps)Model

def build_graph(num_steps,

bptt_steps = 4, batch_size = 200, num_classes = num_classes,

state_size = 4, embed_size = 50, learning_rate = 0.01):

"""

Builds graph for a simple RNN

Notable parameters:

num_steps: sequence length / steps for TF-style truncated backprop

bptt_steps: number of steps for true truncated backprop

"""

g = tf.get_default_graph()

# placeholders

x = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, [batch_size, None], name='input_placeholder')

y = tf.placeholder(tf.int32, [batch_size, None], name='labels_placeholder')

default_init_state = tf.zeros([batch_size, state_size])

init_state = tf.placeholder_with_default(default_init_state,

[batch_size, state_size], name='state_placeholder')

dropout = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [], name='dropout_placeholder')

x_one_hot = tf.one_hot(x, num_classes)

x_as_list = [tf.squeeze(i, squeeze_dims=[1]) for i in tf.split(1, num_steps, x_one_hot)]

with tf.variable_scope('embeddings'):

embeddings = tf.get_variable('embedding_matrix', [num_classes, embed_size])

def embedding_lookup(one_hot_input):

with tf.variable_scope('embeddings', reuse=True):

embeddings = tf.get_variable('embedding_matrix', [num_classes, embed_size])

embeddings = tf.identity(embeddings)

g.add_to_collection('embeddings', embeddings)

return tf.matmul(one_hot_input, embeddings)

rnn_inputs = [embedding_lookup(i) for i in x_as_list]

#apply dropout to inputs

rnn_inputs = [tf.nn.dropout(x, dropout) for x in rnn_inputs]

# rnn_cells

with tf.variable_scope('rnn_cell'):

W = tf.get_variable('W', [embed_size + state_size, state_size])

b = tf.get_variable('b', [state_size], initializer=tf.constant_initializer(0.0))

def rnn_cell(rnn_input, state):

with tf.variable_scope('rnn_cell', reuse=True):

W = tf.get_variable('W', [embed_size + state_size, state_size])

W = tf.identity(W)

g.add_to_collection('Ws', W)

b = tf.get_variable('b', [state_size], initializer=tf.constant_initializer(0.0))

b = tf.identity(b)

g.add_to_collection('bs', b)

return tf.tanh(tf.matmul(tf.concat(1, [rnn_input, state]), W) + b)

state = init_state

rnn_outputs = []

for rnn_input in rnn_inputs:

state = rnn_cell(rnn_input, state)

rnn_outputs.append(state)

#apply dropout to outputs

rnn_outputs = [tf.nn.dropout(x, dropout) for x in rnn_outputs]

final_state = rnn_outputs[-1]

#logits and predictions

with tf.variable_scope('softmax'):

W = tf.get_variable('W_softmax', [state_size, num_classes])

b = tf.get_variable('b_softmax', [num_classes], initializer=tf.constant_initializer(0.0))

logits = [tf.matmul(rnn_output, W) + b for rnn_output in rnn_outputs]

predictions = [tf.nn.softmax(logit) for logit in logits]

#losses

y_as_list = [tf.squeeze(i, squeeze_dims=[1]) for i in tf.split(1, num_steps, y)]

losses = [tf.nn.sparse_softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(logit,label) \

for logit, label in zip(logits, y_as_list)]

total_loss = tf.reduce_mean(losses)

"""

Implementation of true truncated backprop using TF's high-level gradients function.

Because I add gradient-ops for each error, this are a number of duplicate operations,

making this a slow implementation. It would be considerably more effort to write an

efficient implementation, however, so for testing purposes, it's OK that this goes slow.

An efficient implementation would still require all of the same operations as the full

backpropagation through time of errors in a sequence, and so any advantage would not come

from speed, but from having a better distribution of backpropagated errors.

"""

embed_by_step = g.get_collection('embeddings')

Ws_by_step = g.get_collection('Ws')

bs_by_step = g.get_collection('bs')

# Collect gradients for each step in a list

embed_grads = []

W_grads = []

b_grads = []

# Keeping track of vanishing gradients for my own curiousity

vanishing_grad_list = []

# Loop through the errors, and backpropagate them to the relevant nodes

for i in range(num_steps):

start = max(0,i+1-bptt_steps)

stop = i+1

grad_list = tf.gradients(losses[i],

embed_by_step[start:stop] +\

Ws_by_step[start:stop] +\

bs_by_step[start:stop])

embed_grads += grad_list[0 : stop - start]

W_grads += grad_list[stop - start : 2 * (stop - start)]

b_grads += grad_list[2 * (stop - start) : ]

if i >= bptt_steps:

vanishing_grad_list.append(grad_list[stop - start : 2 * (stop - start)])

grad_embed = tf.add_n(embed_grads) / (batch_size * bptt_steps)

grad_W = tf.add_n(W_grads) / (batch_size * bptt_steps)

grad_b = tf.add_n(b_grads) / (batch_size * bptt_steps)

"""

Training steps

"""

opt = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(learning_rate)

grads_and_vars_tf_style = opt.compute_gradients(total_loss, tf.trainable_variables())

grads_and_vars_true_bptt = \

[(grad_embed, tf.trainable_variables()[0]),

(grad_W, tf.trainable_variables()[1]),

(grad_b, tf.trainable_variables()[2])] + \

opt.compute_gradients(total_loss, tf.trainable_variables()[3:])

train_tf_style = opt.apply_gradients(grads_and_vars_tf_style)

train_true_bptt = opt.apply_gradients(grads_and_vars_true_bptt)

return dict(

train_tf_style = train_tf_style,

train_true_bptt = train_true_bptt,

gvs_tf_style = grads_and_vars_tf_style,

gvs_true_bptt = grads_and_vars_true_bptt,

gvs_gradient_check = opt.compute_gradients(losses[-1], tf.trainable_variables()),

loss = total_loss,

final_state = final_state,

x=x,

y=y,

init_state=init_state,

dropout=dropout,

vanishing_grads=vanishing_grad_list

)def reset_graph():

if 'sess' in globals() and sess:

sess.close()

tf.reset_default_graph()Some quick tests

Timing test

As expected, my implementation of true BPTT is slow as there are duplicate operations being performed. An efficient implementation would run at roughly the same speed as the full backpropagation.

reset_graph()

g = build_graph(num_steps = 40, bptt_steps = 20)

sess = tf.InteractiveSession()

sess.run(tf.initialize_all_variables())

X, Y = next(reader.ptb_iterator(train_data, batch_size=200, num_steps=40))%%timeit

gvs_bptt = sess.run(g['gvs_true_bptt'], feed_dict={g['x']:X, g['y']:Y, g['dropout']: 1})10 loops, best of 3: 173 ms per loop%%timeit

gvs_tf = sess.run(g['gvs_tf_style'], feed_dict={g['x']:X, g['y']:Y, g['dropout']: 1})10 loops, best of 3: 80.2 ms per loopVanshing gradients demonstration

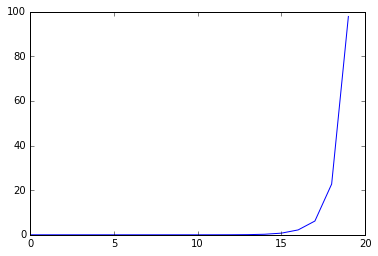

To demonstrate the vanishing gradient problem, I collected this information. As you can see, the gradients vanish very quickly, decreasing by a factor of of about 3-4 at each step.

vanishing_grads, gvs = sess.run([g['vanishing_grads'], g['gvs_true_bptt']],

feed_dict={g['x']:X, g['y']:Y, g['dropout']: 1})

vanishing_grads = np.array(vanishing_grads)

weights = gvs[1][1]

# sum all the grads from each loss node

vanishing_grads = np.sum(vanishing_grads, axis=0)

# now calculate the l1 norm at each bptt step

vanishing_grads = np.sum(np.sum(np.abs(vanishing_grads),axis=1),axis=1)

vanishing_gradsarray([ 5.28676978e-08, 1.51207473e-07, 4.04591049e-07,

1.55859300e-06, 5.00411124e-06, 1.32292716e-05,

3.94736344e-05, 1.17605050e-04, 3.37805774e-04,

1.01710076e-03, 2.74375151e-03, 8.92040879e-03,

2.23708227e-02, 7.23497868e-02, 2.45202959e-01,

7.39126682e-01, 2.19093657e+00, 6.16793633e+00,

2.27248211e+01, 9.78200531e+01], dtype=float32)for i in range(len(vanishing_grads) - 1):

print(vanishing_grads[i+1] / vanishing_grads[i])2.86011

2.67573

3.85227

3.21066

2.64368

2.98381

2.97933

2.87237

3.0109

2.69762

3.25117

2.50782

3.23411

3.38913

3.01435

2.96422

2.81521

3.68435

4.30455plt.plot(vanishing_grads)

Quick accuracy test

A sanity check to make sure the true truncated backpropagation algorithm is doing the right thing.

# first test using bptt_steps >= num_steps

reset_graph()

g = build_graph(num_steps = 7, bptt_steps = 7)

X, Y = next(reader.ptb_iterator(train_data, batch_size=200, num_steps=7))

with tf.Session() as sess:

sess.run(tf.initialize_all_variables())

gvs_bptt, gvs_tf =\

sess.run([g['gvs_true_bptt'],g['gvs_tf_style']],

feed_dict={g['x']:X, g['y']:Y, g['dropout']: 0.8})

# assert embedding gradients are the same

assert(np.max(gvs_bptt[0][0] - gvs_tf[0][0]) < 1e-4)

# assert weight gradients are the same

assert(np.max(gvs_bptt[1][0] - gvs_tf[1][0]) < 1e-4)

# assert bias gradients are the same

assert(np.max(gvs_bptt[2][0] - gvs_tf[2][0]) < 1e-4)Experiment

"""

Train the network

"""

def train_network(num_epochs,

num_steps,

use_true_bptt,

batch_size = 200,

bptt_steps = 7,

state_size = 4,

learning_rate = 0.01,

dropout = 0.8,

verbose = True):

reset_graph()

tf.set_random_seed(1234)

g = build_graph(num_steps = num_steps,

bptt_steps = bptt_steps,

state_size = state_size,

batch_size = batch_size,

learning_rate = learning_rate)

if use_true_bptt:

train_step = g['train_true_bptt']

else:

train_step = g['train_tf_style']

with tf.Session() as sess:

sess.run(tf.initialize_all_variables())

training_losses = []

val_losses = []

for idx, epoch in enumerate(gen_epochs(num_epochs, num_steps, batch_size)):

training_loss = 0

steps = 0

training_state = np.zeros((batch_size, state_size))

for X, Y in epoch:

steps += 1

training_loss_, training_state, _ = sess.run([g['loss'],

g['final_state'],

train_step],

feed_dict={g['x']: X,

g['y']: Y,

g['dropout']: dropout,

g['init_state']: training_state})

training_loss += training_loss_

if verbose:

print("Average training loss for Epoch", idx, ":", training_loss/steps)

training_losses.append(training_loss/steps)

val_loss = 0

steps = 0

training_state = np.zeros((batch_size, state_size))

for X,Y in reader.ptb_iterator(val_data, batch_size, num_steps):

steps += 1

val_loss_, training_state = sess.run([g['loss'],

g['final_state']],

feed_dict={g['x']: X,

g['y']: Y,

g['dropout']: 1,

g['init_state']: training_state})

val_loss += val_loss_

if verbose:

print("Average validation loss for Epoch", idx, ":", val_loss/steps)

print("***")

val_losses.append(val_loss/steps)

return training_losses, val_lossesResults

# Procedure to collect results

# Note: this takes a few hours to run

bptt_steps = [(5,20), (10,30), (20,40), (40,40)]

lrs = [0.003, 0.001, 0.0003]

for bptt_step, lr in ((x, y) for x in bptt_steps for y in lrs):

_, val_losses = \

train_network(20, bptt_step[0], use_true_bptt=False, state_size=100,

batch_size=32, learning_rate=lr, verbose=False)

print("** TF STYLE **", bptt_step, lr)

print(np.min(val_losses))

if bptt_step[0] != 0:

_, val_losses = \

train_network(20, bptt_step[1], use_true_bptt=True, bptt_steps= bptt_step[0],

state_size=100, batch_size=32, learning_rate=lr, verbose=False)

print("** TRUE STYLE **", bptt_step, lr)

print(np.min(val_losses))Here are the results in a table:

Minimum validation loss achieved in 20 epochs:

| BPTT Steps | 5 | ||

| Learning Rate | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.0003 |

| True (20-seq) | 5.12 | 5.01 | 5.09 |

| TF Style | 5.21 | 5.04 | 5.04 |

| BPTT Steps | 10 | ||

| Learning Rate | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.0003 |

| True (30-seq) | 5.07 | 5.00 | 5.12 |

| TF Style | 5.15 | 5.03 | 5.05 |

| BPTT Steps | 20 | ||

| Learning Rate | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.0003 |

| True (40-seq) | 5.05 | 5.00 | 5.15 |

| TF Style | 5.11 | 4.99 | 5.08 |

| BPTT Steps | 40 | ||

| Learning Rate | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.0003 |

| TF Style | 5.05 | 4.99 | 5.15 |

Discussion

As you can see, true truncated backpropagation seems to have an advantage over Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation when truncating errors at the same number of steps. However, this advantage completely disappears (and actually reverses) when comparing true truncated backpropagation to Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation that uses the same sequence length.

This suggests two things:

- Because a well-implemented true truncated backpropagation algorithm would run about as fast as full backpropagation over the sequence, and full backpropagation performs slightly better, it is most likely not worth implementing an efficient true truncated backpropagation algorithm.

- Since true truncated backpropagation outperforms Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation when truncating errors to the same number of steps, we might conclude that Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation does not effectively backpropagate errors the full n-steps. Thus, if you need to capture n-step dependencies with Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation, you may benefit from using a num_steps that is appreciably higher than n in order to effectively backpropagate errors the desired n steps.

Edit: After writing this post, I discovered that this distinction between styles of truncated backpropagation is discussed in Williams and Zipser (1992), Gradient-Based Learning Algorithms for Recurrent Networks and Their Computation Complexity. The authors refer to the “true” truncated backpropagation as “truncated backpropagation” or BPTT(n) [or BPTT(n, 1)], whereas they refer to Tensorflow-style truncated backpropagation as “epochwise truncated backpropagation” or BPTT(n, n). They also allow for semi-epochwise truncated BPTT, which would do a backward pass more often than once per sequence, but less often than all possible times (i.e., in Ilya Sutskever’s language used above, this would be BPTT(k2, k1), where 1 < k1 < k2).

In Williams and Peng (1990), An Efficien Gradient-Based Algorithm for On-Line Training of Recurrent Network Trajectories, the authors conduct a similar experiment to the one in the post, and reach similar conclusions. In particular, Williams Peng write that: “The results of these experiments have been that the success rate of BPTT(2h; h) is essentially identical to that of BPTT(h)”. In other words, they compared “true” truncated backpropagation, with h steps of truncation, to BPTT(2h, h), which is similar to Tensorflow-style backpropagation and has 2h steps of truncation, and found that they performed similarly.